One aspect novice virtual pilots find difficult to grasp is the correct method of flying the aircraft, especially the takeoff, climb and transition to cruise.

The sheer volume of information available on the Internet often results in information overload and it’s understandable that many become bewildered as the boundaries between fact and fiction blur. Add to this that many articles on the Internet have not been peer reviewed, and you have a recipe set for disaster!

In this article, I will instruct on the basic procedures used to takeoff, climb, and transition to cruise. I’ll also provide some insight into how flight crews fly the aircraft, and discuss some of the more important concepts that should be known.

I will not discuss before and after takeoff checklists, the overhead, how to determine aircraft weights, or how to use of the Control Display Unit (CDU). I will assume all essential elements of pre-flight have been completed. Also, the following procedures assume both engines are operational. I will not be addressing engine-out procedures or discussing derates in detail.

Please take note that some procedures are dependent upon what software is used in the Flight Management System (1). Furthermore, the display of specific items, such as the speed reference indicators on the Primary Flight Display (PFD), will only be displayed if the CDU is correctly set-up prior to takeoff.

I have attempted to try and simplify the procedure as much as possible. However, the automated systems that can be used on the Boeing aircraft are complicated, can be used fully or in part, and can easily generate confusion. Add to this that some procedures are different between an automated and manual takeoff, and some procedures are dictated by airline policy.

It is a challenge to simplify what in the first place is convoluted and technical.

I have set out the content in three parts:

Section One refers to a simplified generic procedure for takeoff (numerical sequence 1–20). Below each numerical number are important points (summarized as dot points). Although this section primarily refers to hand flying the aircraft, some automation concepts are discussed.

Section Two discusses takeoff procedures using automation.

Section Three provides additional information concerning important points mentioned in Section One and Two.

To minimise wordiness in this article, I have for the most part, used acronyms and footnotes. Refer to the end of the article for a list of acronyms and their meaning.

Peer Review

The information in this article has been peer reviewed by 737 Captain and First Officer.

Automation and Variability

The Boeing 737-800 can be flown with, without, or partly with automation. The combinations that can be used, how they work, and more importantly when to use them, can fill a book. Indeed, there is a book (two books) – they’re called the Flight Crew Operations Manual and the Flight Crew Training Manual.

The first point to take on board is that there is no absolute correct method for takeoff and climb. Certainly, there are specific tasks that need to be completed, however, there is an envelope of variability allowed. This variability may relate to how a particular flight crew flies the aircraft, environmental considerations (ice, rain, wind, noise abatement, obstacles, etc.), flight training, or a specific airline policy.

Whenever variability is injected into a subject, individuals who think in absolutes - black and white - will have difficulty. If you are the kind of person who likes to know exactly what to do at a particular time, then I suggest you find a technique that fits with your liking and personality.

SECTION ONE: Takeoff Guideline (1-20)

The following procedures assume essential elements of pre-flight have been completed (for example, correct set-up of CDU).

1. Using the Mode Control Panel (MCP), dial into the altitude window an appropriate target altitude, for example 13,000 feet.

2. Command speed is set in the MCP speed window. The speed is set to V2. V2 is determined by calculations made by the Flight Management Computer (FMC) based on aircraft weight, environmental conditions and several other parameters.

Important Points:

V2 is the minimum takeoff safety speed and provides at least 30° bank capability with takeoff flaps set. This speed provides a safe envelope to fly with one engine (if an engine failure occurs).

You can fly either +15 or +20 knots (maximum +25 knots) above the V2 command speed. This is done for a number of reasons: to lower or increase pitch due to the aircraft's weight, or to take into account other environmental variables (this assumes both engines operational), or it is dictated by airline policy.

A white-coloured airspeed bug is displayed at V2 +15/20 on the speed tape (part of the PFD). V2+15 knots provides 40° bank capability with takeoff flaps set. The bug is a visual aid to indicate the correct climb-out speed (bug is discussed later on).

Although not required, it is a good idea is to set the minimums selector to the Acceleration Height as indicated in the CDU. This will place a green line on the altitude tape of the PFD at the height at which the aircraft’s nose is to be lowered and flap retraction to begin. This is a visual aid.

3. Toggle both Flight Director (FD) switches to the O’ position (pilot flying side first).

4. Set flaps 5 and using the electric trim switch on the yoke, trim the aircraft to the correct trim figure for takeoff. The trim figure is shown on the CDU (for example, 5.5 degrees) and is calculated dependent upon aircraft weight with passengers and fuel. Normally the trim figure will place the trim tabs somewhere within the green band on the throttle quadrant. Takeoff should not occur if the trim tabs are outside of the green band.

5. Arm the autothrottle (A/T) by moving the toggle on the MCP to ARM. This may differ between airlines (when to arm the A/T) Consult the FCOM & FCTM.

6. Release the parking brake and manually advance the thrust levers to around 40%N1. %N1 can be airline specific with some airlines recommending 60%N1. Consult the FCOM & FCTM.

7. Monitor the EGT on the EICAS and when there is a decrease in EGT and the throttles are stabilised, either:

Advance the thrust levers to takeoff thrust (if hand flying); or,

Press one or both TOGA buttons if wishing the autothrottle system to be selected. If the autothrottle system has been selected for takeoff, both thrust levers will automatically begin to advance to the correct %N1 output calculated by the Flight Management System.

Interesting Point:

After takeoff configuration is complete, and with the parking brake in the OFF position, some flight crews quickly advance and retard the thrust levers. The purpose being to check for errors in the takeoff configuration. An error will trigger the audible configuration horn when the thrust levers are advanced.

Become conversant with derates. Using a particular derate is normal practice, but in particular will help control over-pitching and high vertical speeds, which are a common occurrence when the aircraft is light (minimal fuel load, passengers and/or cargo).

Important Points:

You do not have to stop the aircraft on the runway prior to initiating 40%N1. A rolling takeoff procedure is often recommended, as this expedites the takeoff (uses less runway length) and reduces the risk of engine damage from a foreign object being ingested into the engine (engine surge/stall due to a tailwind or crosswind).

When the thrust has reached 40%N1, wait for it to stabilise (roughly 2-3 seconds). Look at the N1 thrust arcs and the EGT gauge (on the EICAS display). Both N1 arcs must be stable and the EGT values decreasing slightly. In the real aircraft, the EGT should reduce between 10C-20C after N1 has stabilised at 40%. If the engines are NOT allowed to stabilise, prior to advancing the thrust levers, the takeoff distance can be adversely affected.

There is considerable confusion around when to actually press the TOGA buttons. As stated, %40N1 is common, but some airline procedures indicate 60%N1, while others recommend a staged approach – meaning, initially advance the thrust levers to 40%N1, allow the thrust to stabilise, and then advance the thrust levers to 70-80%N1 and press TOGA.

Do not push the thrust levers forward of the target %N1 - let the autothrottle do its job (otherwise you will not know if the autothrottle system has failed). See Point 10 concerning hand placement.

Ensure the autothrottle has reached the target %N1 by 60 knots ground speed. If not, execute a Rejected Takeoff (RTO).

Unless you select a different mode, the TOGA command mode that was engaged at takeoff (assuming you used the autothrottle system), will remain engaged until you reach the assigned altitude indicated on the MCP.

Selecting N1 on the MCP does not disengage TOGA mode. If you want to disengage TOGA mode, the Flight Director switches must be toggled to the OFF position, or another vertical mode selected.

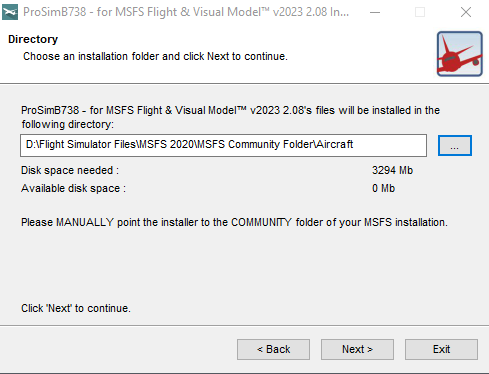

In some simulators that use ProSim737 software (Version 2 & 3), you will notice that when throttle arm is displayed on the PFD, the throttle will retard slightly (%N1). This is NOT normal and is a ProSim737 software glitch. The issue is easily resolved by moving the thrust levers forward slightly. This glitch does not appear to cause other problems.

8. Maintain slight forward pressure on the control column to aid in tyre adhesion to the runway. Focus on the runway approximately three-quarters in front of the aircraft. This will assist you to maintain visual awareness and to keep the aircraft on the centreline. Use rudder and aileron input to control any crosswind.

9. During the initial takeoff roll, the pilot flying should place their hand on the throttle levers in readiness for a rejected takeoff (RTO). The pilot not flying should place his hand behind the throttle levers. Hand placement facilitates the least physical movement should an RTO be required.

10. The pilot not flying will call out 80 Knots Pilot flying should slowly release the pressure on the control column so that it is in the neutral position. Soon after the aircraft will pass through the V1 speed (this speed is displayed on the speed tape). Takeoff is mandatory at V1, and Rejected Takeoff (RTO) is now not possible. The pilot flying, to reaffirm this decision, should remove his or her hands from the throttles; thereby, reinforcing the must fly rule. (see important points below).

11. At Vr (rotation), pilot not flying calls Rotate. Pilot flying slowly and purposely initiates a smooth continuous rotation at a rate of no more than 2 to 3 degrees per second to an initial target pitch attitude of 8-10 degrees (15 degrees maximum).

Important Points:

Normal takeoff attitude for the 737-800 is between 8 and 10 degrees. This provides 20 inches of tail clearance at flaps 1 and 5. Tail contact will occur at 11 degrees of pitch (if the aircraft is still on or close to the ground).

Takeoff at a low thrust setting (low excess energy, low weight, etc) will result in a lower initial pitch attitude target to achieve the desired climb speed.

The correct takeoff attitude is achieved in approximately 3 to 4 seconds after rotation (depending on airplane weight and thrust setting).

Point 10 (above) discusses hand placement during the takeoff roll. Another method used differentiates responsibility between the Captain and First Officer. The Captain as Pilot in Command (PIC) will always have control of the thrust levers, while the pilot flying (First Officer) will concentrate solely on the takeoff with both hands on the control column. Removal of the hand after V1 is a standard operational procedure (SOP). This assumes that the First Officer will be pilot flying.

12. Following takeoff, continue to raise the aircraft’s nose smoothly at a rate of no more than 2 to 3 degrees per second toward 15 degrees pitch attitude. The Flight Director (FD) cues (pitch command bars) will probably indicate approximately 15 degrees.

Be aware that the cues provided by the Flight Director may on occasion be spurious; therefore, learn to see through the cues to the actual aircraft horizon line.

13. At this stage, you most likely will need to trim the aircraft to maintain minimum back pressure (neutral stick) on the control column. The 737 aircraft is usually trimmed to enable flight with no pressure on the control column. It is quite normal, following rotation, to trim down a tad to achieve neutral loading on the control column. Do not trim during the actual rotation of the aircraft.

14. When positive rate has been achieved, and double checked against both the actual speed the aircraft is flying at (see speed tape on PFD), and the vertical speed indicator, the pilot flying will call Gear Up and the pilot not flying will raise the gear to minimize drag and allow air speed to increase. The pilot not flying will also announce Gear Is Up when the gear has been retracted successfully (green lights on the MIP have extinguished).

15. The Flight Director will command a pitch to maintain an airspeed of V2 +15/20. Follow the Flight Director cues (pitch command bar), or target a specific vertical speed. The vertical speed will differ widely when following the FD cues as it depends on weight, fuel, derates, etc. If not using the FD, try to maintain a target vertical speed (V/S) of ~2500 feet per minute.

Important Points:

V2 +15/20 is the optimum climb speed with takeoff flaps (flaps 5). It results in maximum altitude gain in the shortest distance from when the aircraft left the runway.

If following rotation the FD cues appear to be incorrect, or the pitch appears to be too great, ignore the FD and follow vertical speed guidance.

Bear in mind that vertical speed has a direct relationship to aircraft weight - if aircraft weight is low to moderate, use reduced takeoff thrust (derates) or Assumed Temperature Method to achieve a recommended vertical speed.

If LNAV and VNAV were selected on the MCP prior to takeoff, LNAV will provide FD inputs at 50 feet and VNAV will engage at 400 feet.

When VNAV is engaged, the speed of the aircraft will be automatically updated on the speed tape and the speed window on the MCP will become blank.

If LNAV and VNAV have not been selected prior to takeoff, it is common practice to manually select a roll mode (LNAV) at 400 feet. VNAV is usually selected after flaps UP.

If LNAV and VNAV has been selected prior to takeoff. LNAV is advisory. VNAV will automatically update the autothrottle system. The aircraft will not fly the LNAV course or the VNAV vertical profile until the autopilot is selected (CMD) on the MCP.

16. Follow and fly the cues indicated by the FD (automation), or maintain a command speed at V2 +15/20 (hand flying) until you reach Acceleration Height (AH). AH is often stipulated by company policy and is usually between 1000-1500 feet ASL. AH can be changed in the CDU.

17. At or when passing through Acceleration Height, a number of tasks may need to be completed. These tasks will cause the PFD display to change.

The nose of the aircraft is to be lowered (pitch decreased). This will increase airspeed and lower vertical speed. A rough estimate to target is half the vertical speed used at takeoff.

The flaps should be retracted as per the Flaps Retraction Schedule. If noise abatement is necessary, flaps retraction may occur at the Thrust Reduction Height.

Retract flaps as per the Flaps Retraction Schedule. Retract each degree of flaps as the aircraft's speed passes through the next flap increment détente. The flaps increment détente is displayed in green on the PFD speed tape. For example, as the aircraft passes through the flaps 1 designation you would select flaps 5 to flaps 1. Then, when the airspeed passes through the flaps UP position you would select flaps 1 to flaps UP. You do not want to exceed the flaps limit speed. (See Interesting Points (second dot point) regarding the Speed Trend Vector).

Do not retract flaps unless the aircraft is accelerating, and the airspeed is at, or greater than V2 +15/20 - this ensures the speed is within the manoeuvre margin allowing for over-bank protection. Do not retract flaps below 1000 feet RA.

When flaps retraction commences, the airspeed bug will disappear from the speed tape on the PFD.

If hand flying (VNAV not selected), at Acceleration Height set the speed in the speed window of the MCP to a speed that corresponds to the flaps UP speed. The flaps UP speed can be found displayed on the speed tape on the PFD. This is often referred to as Bugging Up.

Some flight crews when reaching Acceleration Height call Level Change, Set Top Bug. This ensures that TOGA speed is disengaged (by selecting another mode).

If VNAV has been selected prior takeoff, the flaps UP speed will be automatically populated and displayed on the speed tape on the PFD. However, the speed will not be displayed in the MCP speed window (the window will be blank).

18. When the aircraft flies through the flaps UP speed, and after the flaps have been fully retracted, the desired climb speed is dialed into the speed window of the MCP (If VNAV is not selected). If VNAV has been selected, the climb speed will be automatically populated and displayed on the PFD (as will the cruise speed when the aircraft reaches cruise altitude).

Important Points:

If VNAV is selected, the speed window in the MCP is blank. However, if VNAV is not selected the speed window is open.

If automation and the autothrottle system (TOGA) is not being used, and you are hand flying the aircraft, Press N1 on the MCP (if desired) at Acceleration Height and follow FD cues to flaps UP speed.

When N1 is selected, the autothrottle will control the speed of the aircraft to the N1 limit set by the FMS. Selecting N1 ensures the aircraft has maximum power (climb thrust) in case of a single engine failure.

If the autothrottle system (TOGA) has been used during takeoff, N1 is automatically selected (by the FMS) at Thrust Reduction Altitude (usually ~1500 feet RA). There is no need to press the N1 button on the MCP.

N1 mode doesn’t control the aircraft’s speed - it controls thrust. The autothrottle will set the maximum N1 thrust (power). The aircraft’s speed is controlled by the pitch attitude.

Selecting N1 on the MCP does not provide any form of speed protection.

Acceleration Height can be changed in the CDU.

The auotpilot should NOT be engaged prior to flaps UP. This is often stipulated by airline policy,

19. The aircraft is usually flown at a speed no faster than 250 KIAS to 10,000 feet. At 10,000 feet, speed is usually increased to 270 KIAS. Environmental factors and/or ATC may result in differing speeds being set.

At this stage, the aircraft can be hand flown with or without VNAV and/or the autothrottle. You can either:

Continue to hand fly the aircraft to altitude. Appropriate climb and cruise speeds will need to be dialed into the MCP; or,

Select a suitable pitch and roll mode (LVL CHG, V/S, LNAV & VNAV) and engage the autopilot or select CWS. If a pitch and roll mode is selected and the autopilot not selected, the FD will provide visual cues.

20. At 10,000 feet, dial 270 KIAS into the MCP speed window and then at 12,000 feet dial in 290 KIAS. Follow the Flight Director cues, or if the FD is not being used, maintain roughly 2000-2500 fpm vertical speed. At cruise altitude, transition to level flight and select on the MCP speed window 290-310 KIAS or whatever the optimum speed is (see CDU).

Interesting Points:

Many pilots had fly the aircraft to 10,000 feet before engaging the autopilot. To enhance situational awareness, it is common practice, if hand flying, to have LNAV and VNAV selected. This enables the pilot to follow the navigation cues displayed on the PFD.

Located on the speed tape on the PFD, is a green coloured line called a Speed Trend Vector (STV). The Speed Trend Vector will display an upwards, neutral or downwards facing arrow. During climb-out, the Speed Trend Vector arrow can be used to determine how long it will take for the aircraft, at the current thrust setting, to reach the speed that the arrow is pointing at (usually around 10 seconds). Therefore, when the upward arrow reaches the flaps indicator, the aircraft will pass through this flaps détente in approximately 10 seconds. The Speed Trend Vector can be used to help know when to initiate retraction of the flaps.

Summary

The above procedures are general. Specific airline policy for a particular airline may indicate otherwise. Likewise, there is considerable latitude to how the aircraft is flown, whether it be without automation selected, or with part or full automation selected.

It is very easy to become confused during the takeoff phase - especially in relation to automation, V speeds, acceleration heights, and how and when to change from hand flying to automation The takeoff phase occurs quickly, there is a lot to do, and quite a bit to remember - there is little time to consult a manual or cheat sheet.

SECTION TWO: Takeoff Guideline (LNAV, VNAV & autopilot selected prior to takeoff)

Although I have mentioned some of the VNAV procedures in the above discussion, I though it pertinent to include this section which will address a takeoff with LNAV and VNAV selected (points 1-10 below). This information relates to FMS software U10.8A.

Important Point:

The following 10 points outline a VNAV selected takeoff:

Select from the CDU a Standard Instrument Departure (SID) and press the illuminated annunciator (EXEC) on the CDU.

Verify the Flight Director switches are selected to the ON.

ARM LNAV and VNAV on the MCP (press the LNAV & VNAV buttons on the MCP).

ARM the Autopilot (press CMD A/B) and set the Command Speed in the speed window of the MCP to V2 (The V2 speed can be found in the takeoff page of the CDU).

Takeoff (as discussed earlier).

VNAV will engage at 400 feet and the Flight Director will command V2 +15/20. The appropriate bugs on the PFD speed tape will be populated automatically. The speed should always be crosschecked against the actual speed that the aircraft is flying and the white bug on the speed tape.

At Acceleration Height (between ~1000-1500 feet RA or as indicated in the CDU) the Flight Director will command a speed 10 knots above the FLAPS UP speed.

Lower the aircraft’s nose and follow the FD cues (command pitch bars).

Commence FLAPS retraction and follow the Flaps Retraction Schedule (Point 18 above).

As the FLAPS retract into the UP position the Flight Director will command 250 knots.

Select CMD A/B (autopilot) or fly to 10,000 feet or cruise altitude and select autopilot.

SECTION THREE: Additional Information - Summarised Important Points

Understanding %N1

To understand the various levels of automation it is important to have a relative understanding of %N1.

N1 is a measurement in percent (%) of the maximum RPM of an engine, where maximum RPM is certified at the rated power output for the engine (most simple explanation). Therefore, 100%N1 is maximum thrust, while 0%N1 is no thrust. (%)N1 will be at a percentage commensurate with the settings that have been inputted to the CDU (aircraft weight, fuel, derates, etc).

Important Points:

The autothrottle logic when TOGA selected controls the aircraft’s thrust (%N1). The aircraft’s speed is controlled by pitch (attitude).

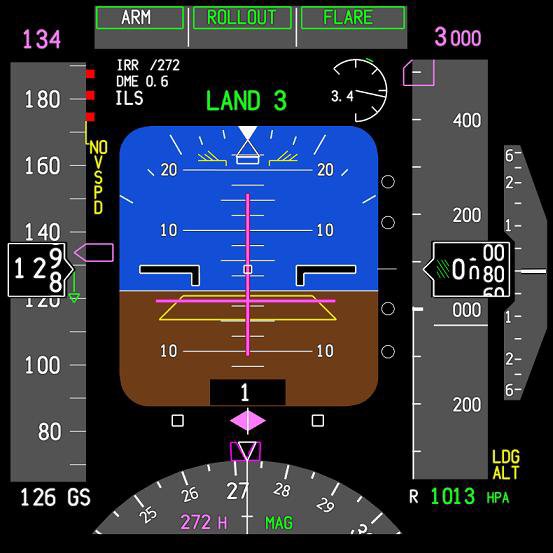

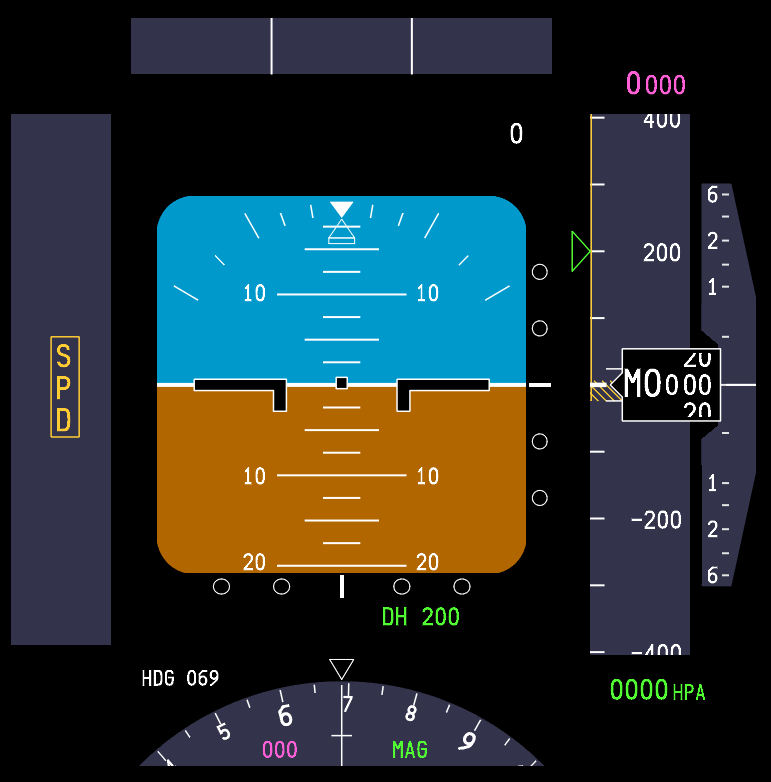

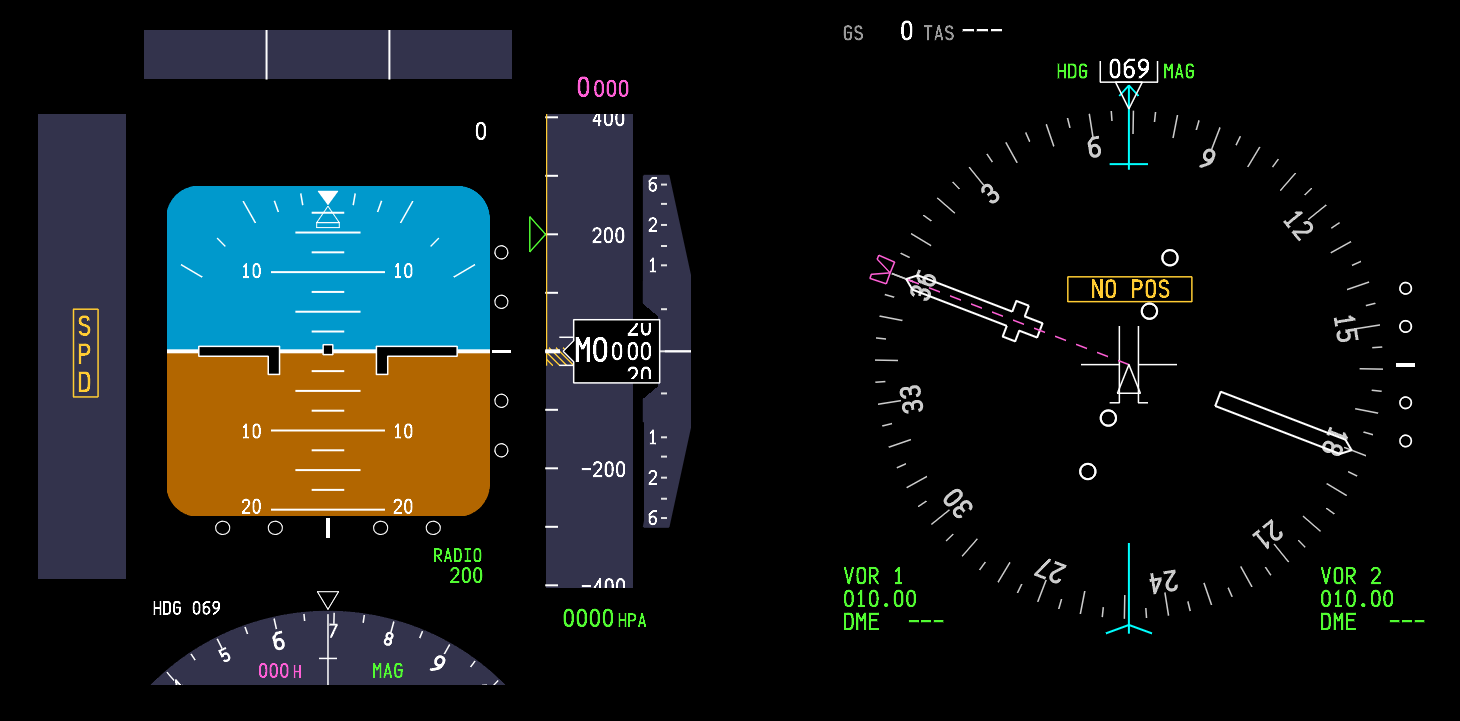

To clarify what automated system is controlling the aircraft, always refer to the Flight Mode Annunciations (FMA) in the PFD (Refer to Table 1 for a quick overview of annunciations displayed during the takeoff).

Common Practice - What to Select For Takeoff

It is not the purpose of this article to rewrite the FCOM or FCTM. Needless to say, there are several combinations, that can be selected at varying stages of flight. All are at the discretion of the pilot flying, or are stipulated as part of airline policy.

After Acceleration Height has been reached, the aircraft’s nose lowered to increase speed, and the flaps retracted, it is common practice to use LVL CHG, V/S, or LNAV and VNAV, and either hand fly the aircraft, select CWS, or select the autopilot (usually at or above 3000 feet, but certainly after flaps UP) and fly to cruise altitude.

If the takeoff does not use LNAV and VNAV (not selected on the MCP) LNAV can be selected at, or after 50 feet RA and VNAV can be selected at, or after 400 feet RA. After either of these two modes have been selected, the Flight Director cues will automatically update to reflect the data that has been inputted into the CDU.

Theoretically, a crew can hand fly the aircraft following the FD cues at V2 +15/20 to the altitude set in the MCP. However, there will be no speed protection, and if the pitch cues recommended by the FD are not followed, then the airspeed may be either below or above the optimal setting or safety envelope. Selecting an automation mode (not V/S) is what engages the speed protection (speed protection will be discussed shortly).

In the above scenario (assuming the aircraft is being hand flown), unless another vertical mode is selected, the aircraft will remain in TOGA command mode (thrust controlled by N1) until the altitude set in the MCP is reached. To deselect (cancel) TOGA as the command mode, another mode such as LVL CHG, VNAV or V/S will need to be selected. Altitude Hold (ALT HOLD) also deselects TOGA as does engaging the autopilot.

Flight crews typically hand fly the aircraft until the flaps are retracted (flaps UP) and the aircraft is in clean configuration. A command mode is then selected to continue the climb to cruise altitude. CWS or the autopilot may or may not be engaged.

Important Point:

It is important to understand what controls the various command modes. For example, LVL CHG is controlled by N1 and pitch. In this mode, the autothrottle will use full thrust, and the speed will be controlled by pitch.